1/20/2025

Late one Friday night, a young man trudged into his kitchen while his wife and infant daughter slept. He heated a cup of coffee and paced the floor. When he placed the cup on his table, his hands trembled

Only 27, this man was a pastor on the rise. He had been asked to lead the local Black community in a boycott of the city’s racially segregated buses. But what was expected to be a symbolic boycott lasting only a few days turned into a 13-month battle that thrust him into the national spotlight.

He started receiving death threats from anonymous callers to his Montgomery, Alabama, home – as many as 40 a day.

After receiving yet another threatening call that evening, the pastor’s resolve crumbled. He slipped into the kitchen that January night in 1956 because he was trying to figure out how he could step aside without appearing to be a coward. Desperate, he prayed aloud to God. “I’ve come to the point where I can’t face it alone,” he said.

Those who study the life of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. know what happened next. King said he was startled that night to hear a voice, urging him to stand up for justice and truth. It was the first time that he’d experienced such a vivid encounter with the Divine.

After that, he said, “I was ready to face anything.” Ten months later, King’s faith was affirmed when the US Supreme Court declared that racially segregated buses were unconstitutional. Montgomery’s buses were desegregated soon after, earning him a huge victory.

This story has long inspired Americans, especially progressives. But almost 70 years later, many people on the political left are struggling with their own moment of despair. On Monday the country will commemorate King’ s national holiday, but this celebration of his life will be unlike any other. It falls on the same day President-elect Donald Trump will be sworn in for a second term.

MLK’s legacy will meet the MAGA movement, on split screens across America. The contrast in their visions will likely be stark — King’s “Beloved Community” vs. Trump’s “American Carnage,” the signature line from his first inaugural address in 2017.

Not long ago, few progressives imagined this day would come. Theyy assumed the MAGA movement had been discredited by the shocking images that emerged from the January 6 insurrection, and that Trump was politically weakened by the barrage of criminal charges against him. Since Trump’s victory in November, though, many of them have veered from anger to disillusionment. Trump will be the first convicted felon to become president.

But King’s example provides a way forward for progressives, say those who knew and study the civil rights leader. Even if you don’t believe in a deity and have never “been to the mountaintop,” King offers lessons in tactics and rhetoric to those who don’t subscribe to a MAGA vision of America.

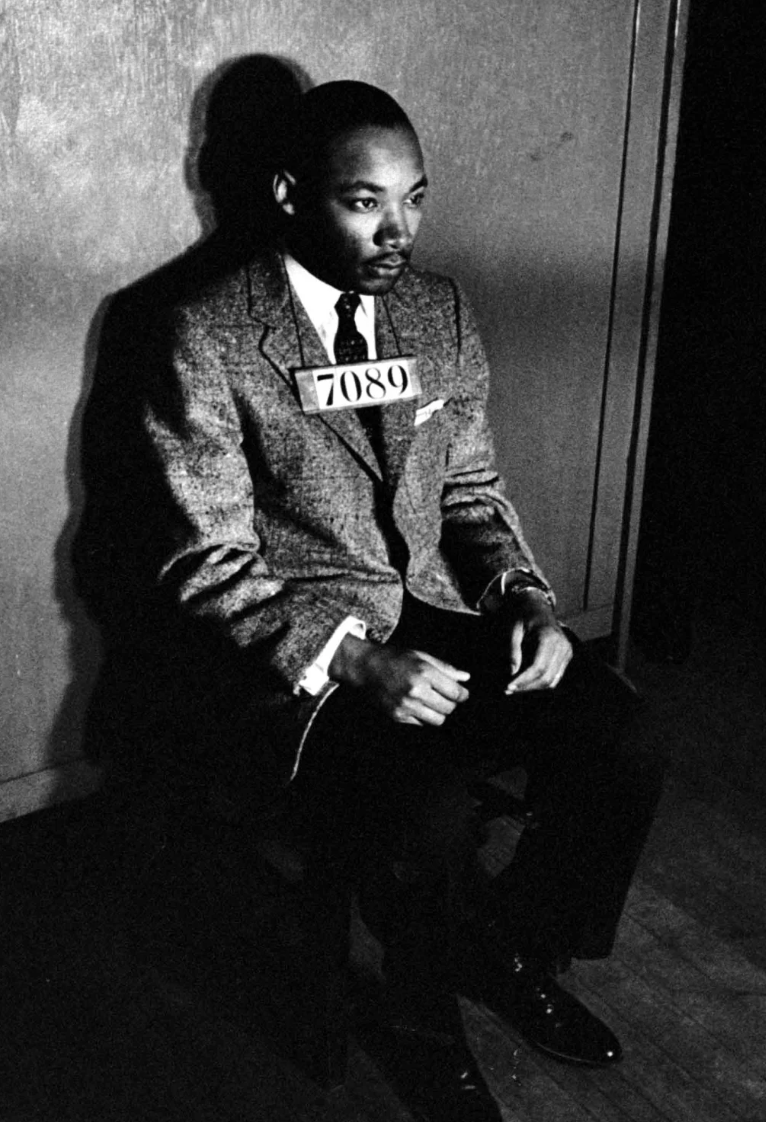

Martin Luther King Jr. poses for a mug shot at a police station in Montgomery, Alabama, following his arrest on February 21, 1956, for directing a city-wide boycott of segregated buses. Don Cravens/The Chronicle Collection/Getty Images

Martin Luther King Jr. poses for a mug shot at a police station in Montgomery, Alabama, following his arrest on February 21, 1956, for directing a city-wide boycott of segregated buses. Don Cravens/The Chronicle Collection/Getty ImagesThe first step involves accepting your anger, says Jemar Tisby, a historian and bestselling author who has studied King and social justice movements.

“Lamenting is part of justice,” says Tisby, author of “The Spirit of Justice: True Stories of Faith, Race and Resistance.” “I don’t think it is healthy as human beings to skip over the grief we feel over our nation and our democracy and jump straight into action. The first step is to feel your feelings.”

And the next steps? Some left-leaning Americans may not want to hear them, because in their fight for social justice and electoral victories, progressives have stepped into traps that King deftly avoided.

King’s legacy offers four uncomfortable lessons for them.

Lesson 1: King rejected narratives of ‘good vs. evil’

This lesson starts with a familiar human emotion: the snub.

This month’s transfer of power in Washington has been filled with snubs. Outgoing Vice President Kamala Harris has apparently decided not to invite her successor, JD Vance, for the traditional, pre-inaugural tour of the vice president’s residence. It comes after a brutal election campaign in which both Vance and Trump attacked her racial identity.

Former Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama also have declined to attend Trump’s inaugural luncheon. (In 2021, Trump didn’t attend Biden’s inauguration after he falsely claimed the election was stolen.) We’ve entered the era of MAD politics — Mutually Assured Disdain.

These political snubs, though, are part of a larger pattern: progressives demonizing Trump and his followers, and recoiling at any contact with them.

Trump tells his supporters that the left views them with contempt, and progressives don’t do enough to challenge that caricature. Leading Democrats have called Trump followers “deplorable” and “weird.” Some progressives have cut off contact with friends or family who support Trump. Many on the left have relentlessly vilified Trump for almost a decade, and it didn’t appear to move the needle among voters in 2024.

Former President Barack Obama talks with President-elect Donald Trump at the state funeral for former President Jimmy Carter at the Washington National Cathedral on January 9. Ben Curtis/AP

Former President Barack Obama talks with President-elect Donald Trump at the state funeral for former President Jimmy Carter at the Washington National Cathedral on January 9. Ben Curtis/APNo less an authority than former President Clinton warned Democrats last year about the risks of demeaning people on the right.

“I urge you to meet people where they are,” Clinton said during a speech at the Democratic National Convention. “I urge you not to demean them, but not to pretend you don’t disagree with them if you do. Treat them with respect — just the way you’d like them to treat you.”

King didn’t need that kind of advice from Clinton. He lived it. Although he endured 13 years of unrelenting scrutiny, it is hard to find mention of King acting in a vindictive or petty way to his critics — even in his private life.

That doesn’t mean King, who grew up in the Jim Crow South, never felt anger. He once said that as a young man, “I was determined to hate every white person.” He grew out of that, though, and later insisted, “Let no man drag pull you so low as to hate him.”

But King rejected reducing social justice movements to “good versus evil” because of his faith and commitment to non-violence. He said, “within the best of us, there is some evil, and within the worst of us, there is some good.”

There was also a strategic calculus behind King’s treatment of his opponents. You can’t win support from a group of people you publicly demean. When you refuse to live down to your opponent’s expectations, you create openings to poach their followers.

Recent elections have shown that plenty of voters on both sides are poachable. Between 7 and 9 million Americans voted for Obama in 2012 and then Trump in 2016. That number is significant for john a. powell, a social-justice advocate and author of “Belonging Without Othering: How We Save Ourselves and the World.”

It means a significant number of Trump voters expressed egalitarian views on race at points in their lives, says powell, who spells his name in lowercase letters.

It’s common for progressives to describe Trump’s followers as irredeemable racists. One Columbia University law student wrote last November that in his academic community, “‘conservative’ or ‘Republican’ is shorthand for stupid, racist, or evil.”

But describing all MAGA followers that way is part of a broader common error, powell says.

“We see ourselves and our own groups in nuanced terms but tend to deny that complexity to other groups,” he writes.

King didn’t make that mistake, powell says. King was what powell calls a “consummate bridger,” someone who was willing to engage with White supremacists, segregationists, Black nationalists — anyone who criticized or despised him. He often listened without overtly trying to change the person’s mind, because he knew that if people felt you listened to them and respected them, you had a better chance to persuade them down the line.

Martin Luther King Jr., President Lyndon Johnson, Whitney Young and James Farmer, from left, discuss civil rights in the Oval Office of the White House on January 18, 1964. GHI/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Martin Luther King Jr., President Lyndon Johnson, Whitney Young and James Farmer, from left, discuss civil rights in the Oval Office of the White House on January 18, 1964. GHI/Universal Images Group via Getty Images“The MAGA movement and the response to it runs away from bridging,” powell says. “It runs into demonizing the other and seeing the other as two-dimensional figures because they don’t agree with you on some issues.”

Diane Nash, a civil rights activist who knew King, was a central figure of many of that movement’s most significant victories. She was a leader in both the sit-in movement and the Freedom Rides, a campaign to desegregate interstate bus travel. She says the nonviolent training she received taught her to not see her political opponents as the enemy.

“The goal is to solve problems and reconcile,” Nash says. “Not speaking to people or hating them is nonproductive.”

Lesson 2: King didn’t just make the civil rights movement about racial grievances

King did something else that sounds counterintuitive today.

“He rejected making the civil rights movement a racial justice movement,” says powell, who is also the director of the Othering and Belonging Institute at UC-Berkeley in California.

Other progressive groups have been burdened by that label. The Black Lives Matter movement gained enormous attention with its stand against police brutality. The group says its work “centers on those who have been marginalized in Black liberation movements.”

But the group’s name doesn’t help, says Taylor Branch, author of “Parting the Waters,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of King.

“The title advertises its limitations. That’s pretty elementary,” Branch says. “But why do they matter to everybody?”

When a social movement is reduced to Black people seeking justice, it’s easier to provoke a backlash. That isn’t fair, but it exists because of another enduring dynamic throughout American history: When Black people gain something, many White people think they automatically lose something in return. They see political struggle as winner-takes-all.

King was aware of that dynamic. He resisted any attempt to reduce the civil rights movement to Black racial grievance. The last campaign he organized, the “Poor People’s Campaign,” was an audacious plan to employ an interracial army of poor white, Black and brown people to occupy Washington. He opposed the Vietnam War and often argued that systemic racism also hurt White people and threatened democracy.

“If you build a movement on grievance you’re playing on Trump’s turf,” Branch says. “He can out-grievance everyone.”

Were he alive today, King would have rejected any movement built on anti-Americanism rhetoric, says Arch Puddington, who worked with Bayard Rustin, a civil rights activist who mentored King.

“Dr. King loved America despite its many shortcomings and made it a personal rule to avoid the condemnation of White people and respect its democratic system,” says Puddington, a senior scholar emeritus at Freedom House, a nonprofit group that promotes democracy and human rights.

“Bayard Rustin often said that he (King) wasn’t interested in psychoanalyzing whites, but rather saw his job as building alliances across racial lines.”

Lesson 3: Hashtag activism is not enough

King was known as a great public speaker, but one of his most significant achievements was his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” The letter is revered not just for its eloquence but for the extraordinary circumstances surrounding its creation.

King wrote the letter while spending several days in solitary confinement in a dark, filthy, jail cell with no mattress in Birmingham, Alabama. He wrote it on bits of balled-up newspapers and toilet tissue that he slipped to his lawyer.

Here’s a question to ponder: What if King had not written the letter in jail? What if he had tweeted it while sitting in his comfortable office with a bag of Cheetos? Or posted it on Instagram along with some dramatic gospel music?

Would it still have the same impact? It’s doubtful. King’s decision to risk his life by voluntarily entering a jail cell gave moral weight to his words. This is a fundamental lesson from King’s life that progressive activists often forget: The revolution will not be digitized. Those who studied and marched with King say you must also put your body where your beliefs are.

Scholars of King don’t argue that online activism isn’t important; they say it’s just not a substitute for in-person activism. At a time when the internet leads more people to spend time alone, it’s easy to forget that lesson.

Tisbsy, the civil rights scholar, notes that the American left hasn’t staged any large-scale demonstrations in the streets since the George Floyd protests in 2020.

“So much of our direct action has been confined to hashtag activism,” Tisby says. “In the same ways civil rights activists did in the ‘50s and ‘60s, we have to consider getting arrested, doing sit-ins, kneel-ins, boycotting and making it known as our last resort if we want things to change.”

And that means people fighting for change close to home, says Tisby, who is also the author of a book for young readers, “How to Fight Racism.”

Activist Ieshia Evans stands her ground while offering her hands for arrest during a protest against police brutality outside the Baton Rouge Police Department in Louisiana on July 9, 2016. Evans, a 28-year-old Pennsylvania nurse and mother of one, had traveled to Baton Rouge to protest. Jonathan Bachman/Reuters

Activist Ieshia Evans stands her ground while offering her hands for arrest during a protest against police brutality outside the Baton Rouge Police Department in Louisiana on July 9, 2016. Evans, a 28-year-old Pennsylvania nurse and mother of one, had traveled to Baton Rouge to protest. Jonathan Bachman/Reuters“Let’s not jump right into Washington,” he says. “Let’s look around to our cities, towns and communities for ways that we can take action.”

In recent years, the limitations of hashtag activism have become more apparent. In a Jacobin magazine essay, Amber A’Lee Frost says it’s difficult to point to tangible lasting victories by such popular movements as #OccupyWallStreet, #MeToo and BLM. She says online activism campaigns “die far too quickly on undemocratic platforms that are corporate-controlled and fleetingly faddish.”

“A desperate activist tweets,” Frost writes. “An aspiring activist uses Facebook. A fledgling organizer emails. An established organizer has phone numbers. A successful organizer is offered addresses.”

Campaigning together in person is also important because of the way human beings are wired.

Watch newsreel footage of the young civil rights activists who participated in sit-ins or Freedom Ride protests and you’ll see them endure the most horrific physical and emotional abuse. But notice how they were together. People draw energy and hope from being with another.

Nash, who was once arrested when she was six months pregnant, said that group bond she shared with fellow activists made all the difference.

“I could not have done what I did without the people I was working with,” Nash says. “It’s foolhardy to think as an individual you’re going to go against the system. You have to do things as a group.”

Lesson 4: Don’t judge a movement’s success by who’s in office

People on the left might look at Trump being sworn in on Monday and think their efforts have failed.

But Nash offers another lesson in dealing with despair. The civil rights movement of the 1950s and ‘60s was filled with failures. Civil rights activists were assassinated, beaten, betrayed by friends, tortured in jail and disowned by their families.

Nash says there were many times she thought of giving up, “but there was too much at stake.” Nash is now 86, but her voice carries steel when she talks about the challenges ahead.

“People have died in large numbers fighting wars to preserve democracy,” she says. “We should not be so foolish as to think we can preserve it without making sacrifices, but it’s worth it.”

If Nash’s words aren’t inspiration enough, King said there’s another solution to despair. He believed every social justice movement has “cosmic companionship” — that God, or some other force in the universe, is on the side of justice.

“I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word,” King said during his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech in 1964. “That is why right temporarily defeated is stronger than evil triumphant.”

Tisby says he turned to that speech after November’s presidential election to jolt himself out of his blues.

“If we make success or failure of our justice work about the externals — a law gets passed, the policy gets changed, who we want gets in office — what happens when we lose?” Tisby tells CNN. “How do you keep going? There has to be something deeper than that.”

A young King found a way to keep going after his dark night of the soul in 1956. Trump’s followers also found a way to keep going after their movement seemed to be derailed in 2021.

So which vision of America will win out in the years ahead — MAGA’s or MLK’s Beloved Community?Whatever happens on Monday won’t give us that answer. But the left might take encouragement from one final piece of knowledge.

King prevailed against many of the challenges progressives face today, but with even less support — and while facing more violence and hatred, his biographer Branch says.

“If King could maintain optimism in his era,” Branch says, “So can we.”

John Blake is a CNN senior writer and author of the award-winning memoir, “More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.”