2/12/2024

Cocoa prices are surging so high that even the biggest chocolate makers are struggling to stay profitable. That doesn’t portend well for your wallet this Valentine’s Day.

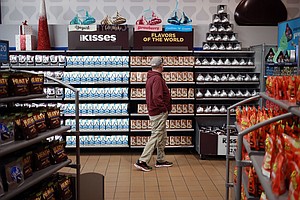

Last Thursday, Hershey Co. said it would cut 5% of its workforce after historic cocoa prices and inflation-weary consumers dampened fourth quarter earnings.

Climate issues in West Africa – home to more than 60% of global cocoa production – are damaging crop yields, constraining cocoa supply and causing prices to soar.

Cocoa futures have skyrocketed, doubling in the past year and surging 40% since January; sugar, labor and other factors have also gotten pricier. That means higher prices down the line for consumers, who will shell out more to fill up on their chocolate treats.

“Cocoa is expected to limit earnings growth this year,” Hershey’s CEO Michele Buck said on a call with analysts Thursday. Hershey’s product prices rose 6.5% in the fourth quarter; prices for their confectionery chocolate and other candy products in North America rose 9% in 2023.

Other companies are feeling the pinch as well. Li-Lac Chocolates, which calls itself the oldest chocolate shop in Manhattan, told CNN that their raw chocolate prices are up 13% this February compared to a year ago.

But Li-Lac has kept the price of one key set of chocolate products flat: “We haven’t raised prices on Valentine’s Day products for our customers since 2022,” the company said in an email.

Billy Roberts, senior food and beverage economist at CoBank, said in a report earlier this month that retail chocolate prices are up about 17% over two years and will continue to rise.

“Cocoa prices are hitting chocolate candy manufacturers really hard,” Roberts told CNN. “And it looks like it’s not necessarily going to subside anytime soon.”

The Supreme Valentine’s Day Sweet

Roughly 92% of Americans say they plan to share chocolate and candy for Valentine’s Day this year, according to the National Confectioners Association. In 2023, Valentine’s Day chocolate and candy sales exceeded $4 billion, the NCA says.

Marnie Ives, the chief executive at Krön Chocolatier in Great Neck, NY, said her business is in the thick of the Valentine’s Day rush.

“On Valentine’s Day we expect about 400 to 450 customers in our retail store every day, which is a lot for a small store,” she said.

Yet Ives said rising cocoa prices aren’t the only concern for her customers this holiday.

“The cocoa prices eventually trickle down and affect us when we’re buying things like bulk chocolate,” Ives said. “But at this level where we’re the last mile of the cocoa beans journey, you know, we have a lot of other things that go into chocolate and confections.”

Ives says her company’s handmade, 4-ounce chocolate bars cost $4 in 2020, $4.50 in 2022 and $5 now. Across the same period, the Consumer Price Index for candy and chewing gum increased 28.3%, outpacing the CPI for all items, which rose 19.4%.

“It’s not just chocolate as the inflationary trigger,” she said, noting price increases are also driven by sugar prices, cocoa butter, packaging and labor costs.

Similarly, Karl Schneider, general manager at Holsten’s Candy Store and Diner in Bloomfield, NJ, said his store has implemented standard price increases to manage costs, and his customers see increases in chocolate prices no different than other prices.

“You know, prices never go down, they never go back to the way they were,” he said. “So, is it a concern? I mean, yes, but we’re going to do the best to make it as cost effective for everyone as we can.”

Roberts’s CoBank report detailed that year over year dollar sales for chocolate confections grew 6.4% by December 2023, while volume sales fell 5%.

“It’s kind of an indication to a lot of manufacturers throughout the industry, not just in chocolate confections, but all over the industry, there’s only so much more room that prices can really grow for your average consumer,” Roberts said.

The outlook for cocoa in 2024

Growing up in Ghana, Issifu Issaka’s parents earned money by cocoa farming. Now 31 and married with one child, Issaka has operated an eight-hectare cocoa farm in the Western North Region of Ghana since 2013. He said that the cocoa production in Ghana depends on the climate.

“Currently because of the climate change conditions, my farm is not producing good,” Issaka said. “I’m not seeing good yield from the farm.”

Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana produce more than 60 percent of the world’s cocoa supply, and climate change concerns there pose risks for cocoa. “This past year, drought in West Africa has led to a compression in the volume of cocoa output, and that has significantly increased prices,” said Will Kletter, vice president of operations and strategy at Silicon Valley startup ClimateAi.

According to data from ClimateAi shared with CNN, shifts in climate patterns could result in a loss of about $529 million in the West African cocoa bean value chain.

Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire could see up to a 30% loss in output, said Sabi Ibarra Guerrero, ClimateAi’s agronomist. These losses are expected to be primarily driven by higher temperatures and intense rain early in the growing season, which increases the likelihood of black pod diseases.

The International Cocoa Organization’s December 2023 market report similarly cited black pod disease and swollen shoot virus as damaging the supply of cocoa crops. “This severe rainfall brings fungi,” Issaka said of his own farm. “And this fungi causes the cocoa pod to be black and you need to spray with fungicide.”

The low supply has driven prices up. But farmers are unlikely to reap the benefits of higher cocoa prices on the international market, according to Uwe Gneiting, a senior researcher at Oxfam America based in Accra, Ghana.

Gneiting explained that futures prices do not translate directly into the farm gate price, which is the price paid to the cocoa farmers. In Ghana, the government sets the farm gate price, and Gneiting said often differing interests between manufacturers and the government prevent farmers from maximizing their earnings.

Issaka said that while high demand and low supply raise prices, cocoa farmers are getting squeezed.

“The price for the cocoa is no good for we the farmers, particularly at the producing country level,” Issaka said.

Joke Aerts is the director of credible scaling for Tony’s Open Chain, an initiative by the Dutch chocolate maker Tony’s Chocoloney to end exploitation in the cocoa supply chain. Aerts explained that it can take a “year or two” for profits from cocoa sales “to trickle down to farmers.”

“The price that cocoa farmers receive in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire should be a price that enables a living income, and currently the farm gate price for cocoa is way below the level that it needs to be,” Aerts said.

Tony’s Chocoloney emphasizes the necessity to pay cocoa farmers the Living Income Reference Price – a price set they developed with Fairtrade that is higher than the farm gate price and aims to calculate the real cost of living for farmers.

According to Tony’s Chocoloney 2022-23 annual report, cocoa farmers in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire currently earn about $1.42 and $1.23 per person per day, respectively. That wage needs to be $1.96 in Ghana and $2.45 in Cote d’Ivoire to be livable, according to the LIRP.

“Cocoa farmers are running away from the cocoa sector and are moving to other areas,” Issaka said. “The youth are not motivated to go into cocoa farming because when they look at their parents, how they’ve suffered for 40 years, 50 years being a cocoa farmer, they are not interested.”

As sales continue, Issaka said he hopes the cocoa farmers can see impactful results from their work.

“The government should make sure that this rising price will get an impact on the pocket of the cocoa farmer,” Issaka said.

But companies are still banking on Americans’ taste for chocolate abiding, especially around major holidays such as Valentine’s Day,