8/13/2019

Updated: 13 AUG 19 09:20 ET

By Jen Christensen and Jessie Yeung, CNN

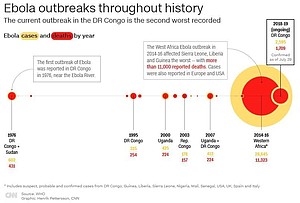

(CNN) -- Two new Ebola treatments are proving so effective they are being offered to all patients in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the current outbreak is the second-deadliest ever.

A randomized trial comparing four different treatments in four towns began in November. Of the four, two treatments known as REGN-EB3 and mAb114 were so effective that researchers announced today they have halted the trial and stopped distributing the others.

These early results suggest scientists are one step closer to curing the disease, which has killed more than 1,800 people in the DRC since last summer.

"From now on, we will no longer say that EVD (Ebola virus disease) is not curable," Jean-Jacques Muyembe-Tamfum, general-director of the DRC's federal medical research institute, told reporters in a call. "This advance will, in the future, help save thousands of lives that would have had a fatal outcome in the past."

Initial results found that 499 patients who received the two more effective treatments had a higher chance of survival -- the mortality rate for REGN-EB3 and mAb114 was 29% and 34% respectively. By contrast, the other two drugs -- ZMapp and Remdesivir -- had higher mortality rates of 49% and 53%.

The two effective drugs worked even better for patients who were treated early -- the mortality rate dropped to 6% for REGN-EB3 and 11% for mAb114, according to Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and one of the researchers leading the trial.

"It means we do have now what looks like treatments for a disease which, not too long ago, we really had no therapeutic approach at all," Fauci said at a press conference.

Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust, a medical research charity, and co-chair of the WHO Ebola Therapeutics Group, said the trial's findings would undoubtedly save lives.

The more researchers learn about the two treatments, "the closer we can get to turning Ebola from a terrifying disease to one that is preventable and treatable," said Farrar in a statement. "We won't ever get rid of Ebola but we should be able to stop these outbreaks from turning into major national and regional epidemics."

Researchers emphasized that these were preliminary results, with further research needed. The groups involved worldwide, which include NIAID and the World Health Organization (WHO), will now conduct an extended study with all patients in the DRC receiving one of the two effective treatments to assess which works best.

Fear and mistrust in local communities

Fighting Ebola in the DRC is made increasingly difficult and risky because of community mistrust, limited health care resources, difficult-to-access locations and violent attacks on heath care workers.

Families would see their relatives go to treatment centers, only to succumb to the deadly disease. So instead of going for treatment, many stayed at home and died, their bodies still highly contagious for the family members who buried them.

These fears and suspicions have even given rise to violence -- there were 130 attacks on health facilities between January and mid-May, causing four deaths and injuring 38.

The two effective drugs could help counteract these fears and suspicions, and make local patients more willing to seek treatment, researchers said on Tuesday.

"If they see 90% of the patients can go into the center of treatment and come out completely cured, they will start believing it and building the trust in the population and the community," said Muyembe-Tamfum.

Yet the findings don't mean the Ebola problem is solved, warned Michael Ryan of the WHO. The two drugs are "a new tool in our toolbox against Ebola, but it doesn't in itself stop Ebola." What's still needed is greater community engagement, vaccination, prevention control, surveillance and the implementation of therapeutic treatments.

"It's not one answer," Ryan added. "But we've taken a huge step forward today."

Researchers working with the WHO and the four pharmaceutical companies that make the drug -- MappBio, Gilead, Regeneron, and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics -- have been racing to stop the Ebola outbreak.

Health workers and DRC officials are on especially high alert -- from July 14 to August 2, four cases of Ebola reached the major transit hub of Goma, which sits right on the Rwandan border.

Before then, Ebola had never reached Goma, which is home to more than 1 million people. Now, health experts fear the virus could make its way across the porous border into still-uninfected Rwanda.

The rare but deadly disease can cause fever, headache, muscle pain, vomiting, diarrhea and unexplained bleeding, among other symptoms. The virus was first identified in 1976 when outbreaks occurred near the Ebola River in the DRC.

Scientists think the virus initially infected humans through close contact with an infected animal, such as a bat, and then it spread from person to person.

The virus spreads between humans through direct contact with an infected person's bodily fluids, including blood, feces or vomit, or direct contact with contaminated objects, such as needles and syringes.