10/13/2017

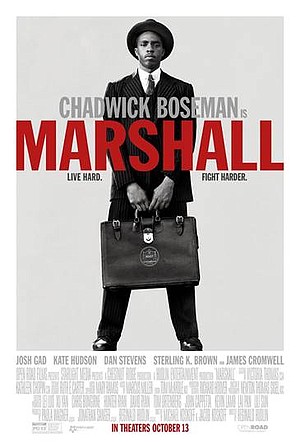

The parallels between the American justice system of say the late 1940s and today aren’t so much different, especially with matters of race. Even as more crime procedurals hit television, real-life has shaped our beliefs of the justice system and a fair deal. Hollywood also knows this. It’s also figured out a way to navigate the space of telling good to great biopics in the same time frame. In “Marshall,” the story of the first African-American Supreme Court Justice and arbiter of the Civil Rights Movement doesn’t roll out a point A-to-B story, or even rundown his life’s work like the re-telling of a Wikipedia page. Instead, the latest Chadwick Boseman starring biopic centers around one of the first significant cases he argued and won.

Reginald Hudlin (“Boomerang,” “House Party”) allows his “Marshall” to play out like an extended crime drama with its lead being a charismatic, stern-voiced gentleman who travels across the country fighting legal battles in the name of the NAACP. Taking on cases for black men tried for crimes they possibly didn’t commit, Marshall’s legal expertise brings him to Bridgeport, Connecticut, a white-crust section of America where a black man is accused of rape and attempted murder of a white, wealthy socialite. There is a bit of paint-by-numbers in the candied version of the trial with Marshall being paired with an unwitting, inexperienced and in-over-his-head co-counsel in Sam Friedman (Josh Gad). But the film shapes Marshall to be the hero, the brilliant and idealistic lawyer and Friedman, his Jewish partner in crime who has to speak for him in court.

What I’ve gathered from every time Boseman dawns the identity of someone else (see Jackie Robinson in “42” or James Brown in “Get On Up”), he flat out embodies the character. Robinson was frank and no-nonsense while dealing with the backlash of being the first African-American ballplayer in the major leagues. Brown, an erratic and problematic showman, found genius in a rhythm only few could see. Boseman’s Marshall feels like a combination of both: a rock star who bends Jim Crow era rules to his whim. He's seen sipping out of “White’s Only” water fountains, berating white people for their crimes against African-Americans and questioning the fabric of the nation for what it has failed to promise all of its citizens. Sounds somewhat familiar to 2017, does it not?

During a select screening earlier this week, Texas State Rep. Jarvis Johnson spoke of the necessity for films such as “Marshall” to be made. “The precedent that Thurgood Marshall set was unbelievable with how he set us on the right path,” Johnson says. “Often times movies aren’t strong enough to send a message to our community. We need a movie like this to remind us that our communities are strong and resilient. The narrative has to be a more positive narrative for our community.“

There are substantial casting jobs all around in “Marshall,” from Kate Hudson’s damsel in distress with ulterior motives to Emmy-winner Sterling K. Brown playing the man accused of ripping her innocence away from her. The set pieces look and feel like the 1940s, where although war is being waged overseas, there’s a building war and understated racism that sticks out rather clear as day. Similar to last year’s successful “Hidden Figures,” Hudlin’s “Marshall” is not shy about displaying the racial overtones of the period front and center. The judge, played by a more than game James Cromwell is still ambivalent to Marshall’s mere presence in the courtroom and would instead stage a pissing contest with Marshall than hear him argue a case he’s more than qualified to debate. The jury? All white. The entire premise feels like a looming set up for a gut punch.

But to drive the effect of the era home, Hudlin finds warmth in some areas and bleakness in others. There are visions of Harlem where Langston Hughes (Jussie Smollett) and Zora Neal Hurston (Rozanda “Chili” Thomas) discuss matters of the day just to show off their mere existence. Boseman’s Marshall walks around with the confidence of a superhero and also the pains of a man who rarely wears his actual life out in public. He has his faults that are Denzelian to a degree, prideful and nuanced yet sometimes blinded by his ambition. Even at the end, before the film bookends itself neatly, there are reminders of today. Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin, the parents of Trayvon Martin, appear as the parents of a Mississippi boy on trial for the murder of a white police officer. In character, they’re repeating the anguish of their real lives with what occurred with their son five years ago.

It’s merely a stickler for how much things haven’t changed.