2/10/2017

The set up for Raoul Peck’s “I Am Not Your Negro” is reflective of the times. Baldwin, one of Black America’s foremost voices on race relations in the 1960s to the point he’s been lionized for all time is made to feel as if he’s speaking for the current. No less than five minutes into Peck’s film are we shown various scenes of anguish and protest from Ferguson, Missouri. It’s the film’s biggest allegory that Baldwin’s work, even when originally framed around the deaths of three of his friends can be echoed for all time.

Baldwin is initially pressed with a question about “negro” optimism and he lets out an exasperated sigh. It's eerily reminiscent of many a conversation Blacks have had in this country in regards to “solving” racism. He responds in kind that it’s not on black people to be the cure for racism. Because black people are constantly aware of something, while whites are far more in line to wistfully ignore it.

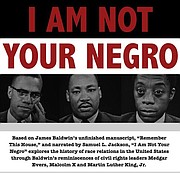

Your cursory idea of “I Am Not Your Negro” is not a crash course into James Baldwin, the man. It is a film based around Baldwin’s thoughts from an unfinished manuscript. The 31 pages of “Remember This House” play out as a letter to a friend, with Samuel L. Jackson’s voice operating as the main vehicle of Baldwin. As a literary titan, Baldwin’s views of the world have been captured in “The Fire Next Time” and archived speaking engagements across the globe. He was the fearless one, even when the FBI had a watch on him as if he were a fire-stroking revolutionary.

Peck, whose previous work included 2000’s “Lumumba” decides to take viewers on a bit of a history lesson, showing the parallels between the 1960s Civil Rights Movement and the #BlackLivesMatter movement of today. Creating a movie with Baldwin involved him contacting the estate. “His sister had seen my film. “Lumumba” and when I asked for the rights, she agreed to everything, which was unprecedented.” It would be four years before he had any grasp on how to present “I Am Not Your Negro” before finally settling on the work of “Remember This House”.

Death as it were is a far greater muse than we let it on to be. Baldwin knew the subjects of “Remember This House” intimately as good friends. None of the three main subjects, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X & Martin Luther King Jr., lived past the age of 40. Lorraine Hansberry, who died at 34 from pancreatic cancer was a minor vehicle for Baldwin in the manuscript. He mourned her death, opining on the idea that she was a victim of the fight for equality. A playwright, fearless, had smoked more than three packs a day. The weariness that bore on Baldwin in the 31 pages of “Remember This House” are echoed today.

The beliefs and accolades lobbed towards the now Oscar-nominated film are strong, if not astute. How Peck chooses to jump around with the timeline to show the parallels is concise editing. His parallels aren’t completely direct, there is no modern take on how whites and others attempt to dictate race control upon blacks. But there is archival and historical footage of how black men are depicted. Of how horror films of their time were actually crime dramas where black men were found guilty before their peers. There’s anguish over the death of Emmitt Till, his grisly lynching still bearing scars some fifty years later. Lies still hang heavily upon the constant view of Black America, even as unrepentant racism and more has not only tugged on America’s skirt, it has disrobed her completely.

“It's scary for the younger generation because you don't have the models right in front of you,” Peck told MTV in a recent interview. “There's an apparent freedom, an apparent liberty of access to everything, but you can't use it because it's too much. I don't know how it's gonna go, but like Baldwin says, this generation will need to face it. You can't put your head in the sand and pretend it doesn't exist. The best way we know is to face it and start talking — really talking, face to face.”

When race battles occurred in Alabama, they were broadcast on the news nightly. Baldwin viewed the apathy towards it not as alarming, but rather another notch towards the belief of general white apathy. “White people wish Birmingham was on Mars, naive to the fact that Birmingham is occurring all over the country,” he says in the film. It’s a theme that’s been broached not only in “I Am Not Your Negro” but across the annals of time. Segregation of the races was never about acknowledging how the other half lives, it was about being obtuse to how the other half suffered.

“Most of the white Americans I’ve ever encountered had a Negro friend or a Negro maid or somebody in high school,” Baldwin says during the film in a clip taken from his 1963 lecture at the Florida Forum. “But they never or rarely, after school was over or whatever, came to my kitchen. We were segregated from the schoolhouse door. Therefore he doesn’t know, he really does not know, what is was like for me to leave my house, you know, leave the school and go back to Harlem. He doesn’t know how Negroes live. And it comes as a surprise, to the Kennedy brothers and to everybody else in the country. I’m certain, again, like most white Americans I’ve encountered. They have no, I’m sure they have nothing against Negroes. That’s really not the question. The question is really a kind of apathy and ignorance. Which is a price we pay for segregation. That’s what segregation means. That, you don’t know what’s happening on the other side of the wall, because you don’t want to know.”

Peck’s film is mandatory viewing. Not for it’s appeal to the non-woke, but how it essentially picks up where Baldwin left off. Jackson’s voice, normally alarming and animated is smoldering, if not a cold reminder of gravitas. His duty as a director was to give light to the days of old and the current of new.

As protests erupt across the country against the current administration that inhabits the house at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, there’s a conversation to be had about the major vehicle that roamed in Ferguson: protest. Protesting in Ferguson after the death of Michael Brown began occurring across the country for a number of unarmed Black men and women at the hand of the police. However, they weren’t given the same coded language of resistance and championing by the media and others. Instead, they were dehumanized, reduced to misnomers and more. There’s a parallel with that as well.

“The white revolutionary sounds far more romantic, than the black one,” Baldwin says. As a man far ahead of his time, as someone who operated as a witness rather than an agent to the Black Panthers or the Black Muslims, I wonder if he knew how much his words would echo throughout decades, if not a half century. “I Am Not Your Negro” is not the piece of art that shall change a world but it’s a film that works as a time capsule into both the past and the future. When the thundering drums of Kendrick Lamar’s “The Blacker The Berry” bring up the credits, we’re left to question where exactly did we go. And how far do we still have to go.